So it’s finally happened – you’ve gotten the long awaited

acceptance letter. After a string of rejections, what a relief to see

confirmation that your work is ready to be read by the world! This is the big

moment when you get to celebrate seeing your name in print (and of course,

seeing your name in print on a paycheck as well).

If you’ve done your research, you should know already what

your contract is going to look like when it arrives from the publisher. But do

you really understand what all that jargon means? Now is not the time to just

sign your name in glee and skip over the fine print. Bad things still happen to

authors who aren’t careful, and inexperienced writers may discover too late

that they are not actually 100% on board with the terminology in their

contract. This is why it is very important to not only submit your work to

trusted markets, but to also do the research it takes to understand the end

product.

Let’s dive into the basic categories of rights that you will

see on most of your publishing contracts.

First Rights

First Rights in general are pretty much self-explanatory.

The journal or publishing house that is purchasing your work is purchasing the

right to distribute the story first.

The term First Rights is a large umbrella under which many other sub-categories

exist, but we’ll go through some of those later.

It is very important to understand that, even though First

Rights seem simple, many publishers are divided on what constitutes a work as

published or not. You can’t sell the exclusivity of something that has already

been let out of the bag, so be careful with what you do while you’re waiting to

sign a contract! Some publishers are very strict and will count any distribution

of the work as the loss of your First Rights. Once you’ve sold your First

Rights, the only other right you’re going to be selling is for reprints. This

severely narrows your ability to sell the story, since reprints are not the top

priority of many publishing houses.

A good rule of thumb is, when in doubt, hold on to your

work. Cater to the harshest critic and you will have no trouble selling to a

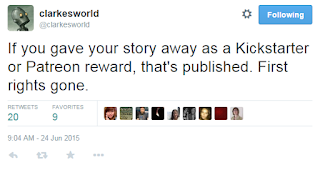

more lax editor. Neil Clarke (of Clarkesworld magazine) tested the waters on this

controversy via a twitter conversation recently, and you can see that some share his strict

point of view, while others would make exceptions. Later on he produced a

webpage narrowly defining some examples of what constitutes a work as published

or not. I highly recommend reading these rules before you make any attempts to

distribute your work on your own.

Subsidiary Rights

As mentioned before, First Rights is a very broad term that

covers a variety of subset rights. If you’re selling Exclusive or Unrestricted

First Rights, this means that you are selling the rights for all possible

subsets.

Rights can be determined based on language, geographic

location, type of distribution, etc. If you are seeking publication in an

American or Canadian literary journal, you are likely going to run across the

term “First North American Serial Rights.” This terminology is giving the

publisher the exclusive right to distribute the work to a North American

audience via a Serial publication (the magazine).

Some publishers will also request the rights to

audio/podcast versions of the work, or even sometimes video representation.

They may also throw in the right to publish the work in an anthology later on.

If you’re looking at all these restrictions and starting to

feel a little panicked, don’t worry. Remember, you ultimately own the copyright

of your work. You are simply selling certain features of it for a set amount of

time in very specified forms of media. Most publishers will only claim

exclusive rights of any type for a short period of time (for example, one

year). After that the rights become unexclusive and no longer have any bearing

on where you choose to reprint the work (unless this too was restricted in your

contract – so read the fine print!).

Also remember that once you sell even one subset of rights,

you can no longer sell your work to anyone who is looking for exclusive first

rights. So if a friend of yours wants to make an audio version of your story

for their weekly podcast, remember that will have an impact on whether or not

you can seek publication in print!

For a much more thorough breakdown of terminology that you

might come across, check out these awesome guides from The Internet Writing

Journal, Writing-World, and Poets&Writers:

Some other useful sources are Lightspeed Magazine’s Contract Template for Original Fiction, as well as author Nathan Bransford’s breakdown

of a basic publishing contract.

Questions? Let me know in the comments and I’ll be happy to

answer them for you. Happy submissions to you all!

No comments:

Post a Comment